So, you’ve been to your doctor/physio & they’ve reassured you that nothing serious or harmful is going on, but you still have pain

For many of us pain is an inevitable part of life. Whether it’s breaking a bone, spraining an ankle, or just waking up with a stiff and painful neck wondering what happened in your sleep.

The International Association for the study of pain (IASP) define pain as:

“An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with or resembling that of actual or potential tissue damage.”

The key parts reflected in this definition are “actual or potential tissue damage”, meaning that although we may experience pain at times it is not a definitive guarantee that we have damaged our tissues.

All over our bodies we have danger detecting nerve cells, which alert us to potential threats to our body. When these nerves get activated under the right circumstances it may lead to a painful experience.

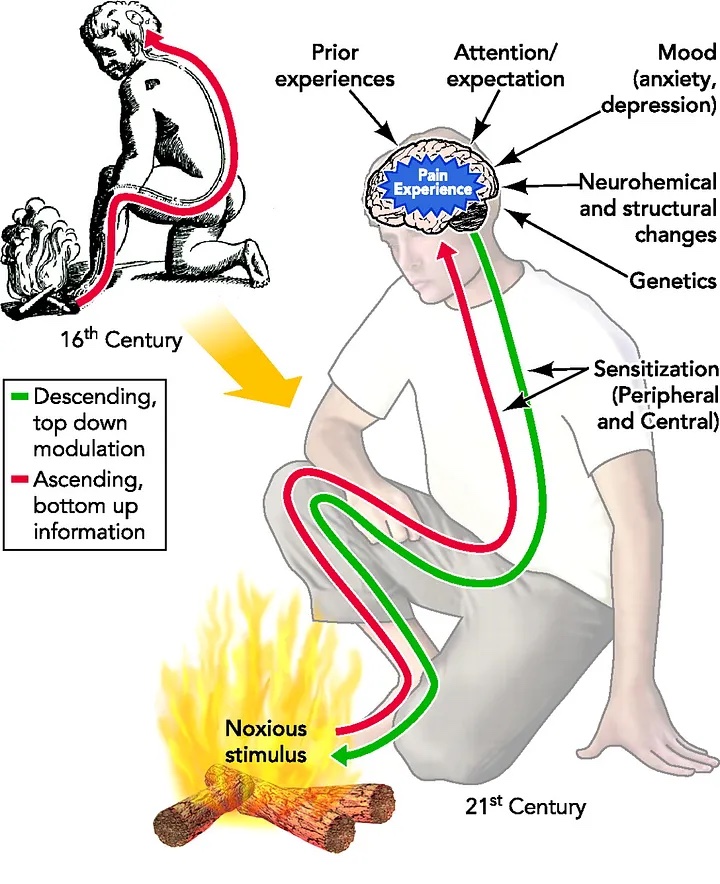

Historically this was viewed as a one-track road where the activation of these danger receptors meant that we experienced pain as shown in the figure below (foot in the fire sends messages along “pain pathway” to produce painful experience).

Thanks to decades of scientific research, we now know that it is far more complex than this.

Additionally, the environment where you are in plays a crucial role. For example, if an injury were to occur in a life-threatening situation, pain induced by the injury would take second priority in order to ensure survival. The main takeaway from this is that our nervous system and tissues are body involved during a painful experience.

Figure from Sabatowski et al (2004)

Ultimately pain serves as a protective system designed to save us from causing further harm to ourselves. But just like things can go wrong in other bodily systems (think breathing system after catching a cold, or our digestive system after eating something funky) our pain system can have issues as well.

Our pain system can become dysfunctional in one or two ways; the first is our system not producing enough pain. Some individuals have the unique ability to not experience pain at all, known as congenital pain insensitivity. A life without pain may sound like a dream, but unfortunately these people do not learn from the lessons that pain teaches us and often get seriously injured because of this.

The second way is that it produces too much pain or our “pain alarm” becomes too sensitive.

When this happens moderately painful experiences can become extremely intense and sometimes things that aren’t meant to hurt us, such as our clothes rubbing against our skin or normal movement of a body part are now painful.

This intense pain experience can be highly distressing and cause emotions such as anxiety, fear, and stress. It can also disrupt our sleep and interfere with our daily lives, further impacting on our ability to function.

The pain may also stop you from the things you love such as sport or socialising with friends and family to shield ourselves from further increases in pain. These factors can all lead to a maintenance of pain and a significant decrease in quality of life. Although this pain can be quite unbearable, it does not accurately reflect how much damage you have done to your body.

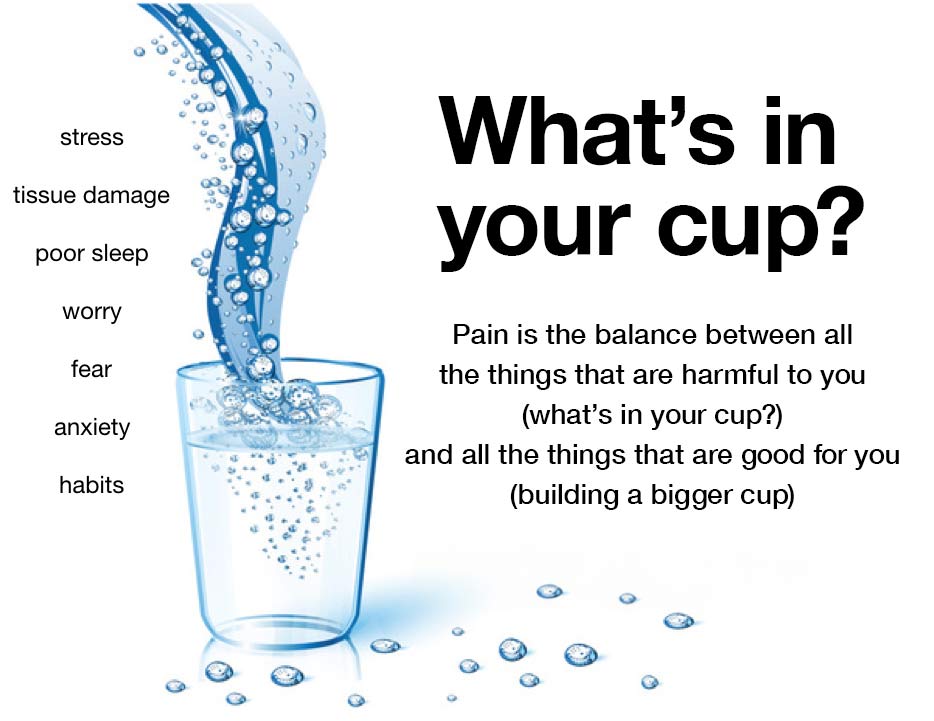

Knowing all the different contributors and triggers to your pain can be extremely beneficial in managing it and knowing how to best create a healthy environment for your body. This is summarized in the figure.

Once any serious harm or condition has been ruled out things that can help reduce the alarm sensitivity include; being optimistic about our ability to recover, doing gradual movements working towards things we are avoiding, monitoring alcohol intake, getting enough sleep, monitoring our stress levels, maintaining a balanced diet and exercise (whether its yoga, going to the gym, cycling, or swimming, they can all be beneficial!).

This blog has attempted to provide a basic explanation of what pain is and how we can manage it. Pain is extremely complex in nature and always has biological (tissues), psychological (nervous system) and social (environmental) meanings attached to it. So, if you find yourself experiencing aches and pains think about other contributors to why our body might be feeling sensitive such as a bad night’s sleep, a stressful period you’re going through, or whether you’ve done too much or not enough movement & look at some of the above ways to help yourself feel better. Any pain causing a great deal of concern or if abnormal symptoms such as fever, redness and swelling are present. should seek further medical evaluation.

Reference List

Raja, S. N., Carr, D. B., Cohen, M., Finnerup, N. B., Flor, H., Gibson, S., Keefe, F. J., Mogil, J. S., Ringkamp, M., Sluka, K. A., Song, X.-J., Stevens, B., Sullivan, M. D., Tutelman, P. R., Ushida, T., & Vader, K. (2020). The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain, 161(9), 1976–1982

Sabatowski, Rainer, Daniel Schäfer, Stefan-Mario Kasper, Holger Brunsch, and L Radbruch. 2004. “Pain Treatment: A Historical Overview.” Current Pharmaceutical Design 10 (7): 701–16.

Melzack R, Katz J. Pain. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2013;4(1):1-15.

Talaei-Khoei M, Ogink PT, Jha R, Ring D, Chen N, Vranceanu AM. Cognitive intrusion of pain and catastrophic thinking independently explain interference of pain in the activities of daily living. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;91:156-63.

Bjorklund G, Aaseth J, Dosa MD, Pivina L, Dadar M, Pen JJ, et al. Does diet play a role in reducing nociception related to inflammation and chronic pain? Nutrition. 2019;66:153-65.